Aries i: Hades

Welcome to the first post of my Deities and Decans series! Today we’ll be talking about Hades, the deity associated with the first Decan of the zodiac, Aries I. My hopes with this post — and the rest in the series — is to help create a stronger link between each decan’s deity and the story of each decan. We’re lucky to have so many brilliant astrologers looking into the Decans more profoundly in the present, and I think that highlighting the deities of each decan will only help to enrich our knowledge on this topic further. So without further ado, let’s dive in!

The King of the Underworld

Hades (aka Aïdēs, Aidoneus, Plouton) is the god of the Underworld, responsible for overseeing those who leave the earthly realm and deciding what kind of time their souls will be having under his rule. In Greek mythology, he doesn’t really seem to possess main character energy, but he still plays an important role, showing up many times in the stories of Heroes like Heracles, Orpheus and Perseus, to name a few.

As far as how the Underworld itself was set up, in the Odyssey, it was originally said to be a vast, gloomy grey field for the dead, with a place called Tartarus which was only reserved for sinners fated with a special punishment. As time went on, it was separated into three parts: Elysium (Isle of the Blessed), Tartarus (for criminals and sinners), and the Fields of Asphodel (Hades). The souls who enter the underworld would be judged by Hades, and placed into one of these three categories. If you’ve read my previous article on the Gates of Hades, you know that I often associate the word “judgement” with Hades and the set-up of the Underworld mirrors this notion.

L’Enlèvement de Proserpine (1767) by Joseph-Marie Vien

Like I’ve said before in my 2H profection year article, Hades is a pretty altruistic deity all things considered. He doesn’t meddle in earthly matters for the most part, and tends to keep to himself in the Underworld. He takes his job seriously, and doesn’t see a need to insert himself in the matters of other Olympian deities if unprovoked. Even in his most controversial myth involving the abduction of Persephone, he still acknowledged and respected the Olympian chain of command and asked permission from his brother, who is also Persephone’s father, before taking action. Despite this fact though, the focus in popular culture tends to be on the kidnapping itself and the modern consensus is “that was bad.”

This isn’t necessarily an incorrect assessment, but it is quite reductionist considering that it 1) personifies a deity and 2) ignores the fact that Hades followed the rules and did right by the boss and his brother, Zeus. He holds himself to the same standards as his subjects in the Underworld, insofar as he knows what — and who — will actually get him in trouble and what to avoid doing to put himself in a bad position with the One in power. He might be indifferent to Earthly matters, and thus may not care that Demeter wreaked havoc when he kidnapped her daughter, but Demeter doesn’t call the shots on Mount Olympus — Zeus does — so that’s who he appeals to. In our present day it might not seem just or fair, but Hades simply operates from the set of rules given and enforced by Jove; very Kantian in a sense.

Hades and the Axe

Ancient Greek bronze axe head (Classical period)

Being named « The Axe » by Austin Coppock, Aries I is definitely the decan of controversy. We can dress up an axe whichever way we’d like, but at the end of the day it is there to cut and sever — to varying degrees. The axe itself was even used as a scapegoat in ancient times, as people would put an axe on trial for « killing » an ox, for example. This wasn’t because people thought the axe actually killed the animal, but because the person who did do it (often a priest performing a ritual) knew it was a crime to sacrifice an ox, and ran for the hills the second he made the sacrifice to escape arrest. Someone had to be held responsible for the crime, so they found the guilty party, albeit an inanimate object that can do no harm on its own.

The axe, just like Hades, has an unglamorous job to do, but it is necessary work nonetheless. This is where we see the myth of Hades intersect the story found in Aries I. This decan and its deity both possess this controversial quality, that plays out regardless of one’s intentions. With Aries I being a double Mars ruled decan, it’s no wonder that natives possessing placements here emit strong martial energy and often create friction in certain areas of their lives as a result. However, an axe can also be a useful tool if interacted with properly; we just have to have the skills and knowledge to know what to do with it, in order for it to benefit us.

Hades also has a more approachable side to him, which is why the ancients also referred to him as Plouton, meaning « wealthy. » This is because the wealth in ancient times was often found underground in the forms of crops, precious stones, and metals which was believe to be found outside the Gates of Hades. Though Hades was scary to most, he was also a deity that had to be worked with and appeased in order to obtain the wealth we often associate with Zeus/Jupiter. This is why I often think of the phrase « getting your hands dirty » when I think about Hades and Aries I; the unpleasant, ugly tasks of a goal take us where we want to go, even if it sucks to admit it. You can’t have a blooming garden, reach your body goals, or perfect your craft, without doing the annoying and tedious work, just like the ancients couldn’t perform certain rituals successfully without using the blade for sacrifices. However, all of these actions are necessary to obtain the envisioned — and often positive — end-goal.

Aries I example: Gavrilo Princip

Natal chart of Gavrilo Princip

When I was doing my research for this post, my mind often went to the infamous Gavrilo Princip and how his assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand d’Este was the catalyst for starting the First World War. Never having consulted his chart in the past, I looked it up and sure enough, Gavrilo had his North Node in Aries I.

From an outside perspective, Gavrilo was a murderer and political agitator of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; which is very Aries I on its own. However, upon a deeper analysis you come to realize that Princip was a part of an oppressed demographic who desired to be freed from their rulers. Having been born in what is today Bosnia and Herzegovina, Gavrilo along with his fellow Bosnian/Serbs were seen as illiterate and insignificant by the ruling class. Before the assassination, you’d typically see him pictured holding books, not because he was a bookworm, but because doing so was seen as an act of rebellion against the A-H Empire.

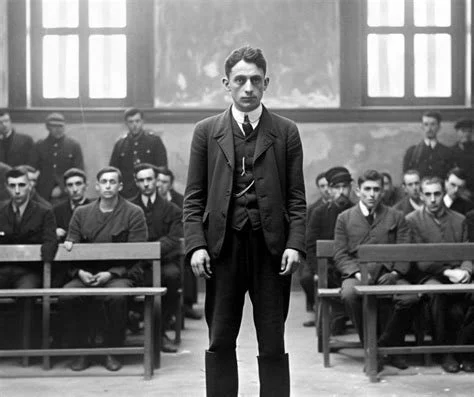

Gavrilo Princip pictured standing at the front of his class

In 1911, after moving to a more sophisticated high school referred to as a « gymnasium, » Gavrilo joined Young Bosnia, which was a secret local society with an aim to free Bosnia from A-H rule and unite the Southern Slav population. After being expelled from his school for attending anti-Austrian protests, Princip walked to Belgrade Serbia to continue his education. Though he had the desire to fight the Ottomans in the South of Serbia during the First Balkan War, he was ultimately rejected due to his size and lack of physical strength.

Princip was initially never meant to kill the Archduke by himself, but it was rather fate (hello, North Node!) that brought him into that defining moment for both himself and the rest of Europe. Upon the Archduke’s assassination Princip was quickly arrested and charged with high treason and murder. At his trial he was outspoken about the unification of Southern Slavs and stated that it didn’t really matter how the unification occurred, he just wanted Slavs to be freed from A-H rule. Princip died in custody from tuberculosis on April 28, 1918, as his conditioned worsened even after amputating his right arm.

Though WWI was a long and brutal war — especially for the Serbian male population — in the end Gavrilo got his wish, as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was formed in 1918 after the war ended. His legacy has since been a controversial one; for the A-H Empire, and later on by the Nazis in WWII, Princip was seen as a ruthless terrorist and anarchist, but for the Yugoslavian population he was seen as a hero of armed resistance. Even today, when you ask people about him you’ll always have a mixed bag of responses, whether it be in the nations of former Yugoslavia or abroad. I guess that controversial edge never truly escapes those with placements in Aries I, just as it never truly escaped Hades either.